Diving into the world of whole wheat baking can feel like unlocking a new level in your kitchen adventures. It’s more than just swapping out white flour for its heartier cousin; it’s about understanding a different kind of ingredient, one that brings nutty flavors, a denser crumb, and a boost of fiber and nutrients to your favorite baked goods. While the results can be incredibly rewarding – think rustic loaves, wholesome muffins, and satisfying cookies – getting there sometimes involves a bit of a learning curve. Don’t be discouraged if your first few attempts aren’t perfect! Whole wheat flour behaves differently, and knowing what to expect is half the battle.

The primary difference lies in the composition. White flour is milled from just the endosperm of the wheat kernel. Whole wheat flour, true to its name, includes the entire kernel: the starchy endosperm, the fibrous bran, and the nutrient-rich germ. It’s the bran and germ that give whole wheat its characteristic color, flavor, and nutritional punch. However, these components also interfere with gluten development – the protein network essential for trapping gases and giving bread its rise and chewy texture. The sharp edges of the bran can physically cut through gluten strands, leading to denser, heavier results if not managed correctly.

Understanding the Challenges

So, what are the main hurdles? First, as mentioned, is

density. Because the bran and germ hinder gluten formation, whole wheat doughs often don’t rise as high or have the same light, airy texture as those made with white flour. Second, whole wheat flour is

thirstier than white flour. The bran and germ absorb more liquid, which means you’ll usually need to adjust the hydration levels in your recipes. Using the same amount of liquid as you would for white flour often results in a dry, stiff dough and, ultimately, a crumbly baked product. Third, the flavor can be quite pronounced, sometimes described as nutty or even slightly bitter, which might overpower more delicate flavors in certain recipes.

Hydration is Key

Getting the moisture content right is arguably the most critical factor. Since whole wheat absorbs more liquid, you’ll generally need to increase the water, milk, or other liquids in your recipe by a bit. How much? It varies depending on the specific flour (different brands and grinds absorb differently) and the recipe itself. A good starting point is to add an extra tablespoon or two of liquid per cup of whole wheat flour substituted. Aim for a dough that feels slightly wetter or stickier than you might be used to with white flour. It will firm up as the bran and germ absorb the liquid during resting and kneading.

Whole wheat flour absorbs liquid more slowly than white flour. Allow your dough or batter to rest for 10-20 minutes after mixing. This hydration rest gives the bran and germ time to soften. Properly hydrated bran interferes less with gluten development.

Techniques for Lighter Results

While a 100% whole wheat loaf will naturally be denser than a white loaf, there are several techniques you can employ to achieve a lighter crumb and better rise.

1. The Autolyse Method

This sounds fancy, but it’s simple. Combine just the flour and water (or liquid) called for in your recipe and mix until just combined – no dry patches should remain. Cover the bowl and let it rest for 20 minutes to an hour before adding the yeast, salt, and other ingredients. This rest period allows the flour to fully hydrate without the interference of salt (which can tighten gluten) or yeast (which starts fermentation). The enzymes in the flour begin to break down starches and proteins, kickstarting gluten development and softening the bran, leading to a dough that’s easier to work with and yields a softer crumb.

2. Combining Flours

You don’t have to go all-in right away. Start by substituting a portion of the white flour with whole wheat. Replacing 25% to 50% of the white flour is a great way to introduce whole wheat’s flavor and nutritional benefits without drastically changing the texture. Gradually increase the percentage as you get more comfortable. For many recipes, like cookies or muffins, a 50/50 blend offers a nice balance.

3. Adding Vital Wheat Gluten

For bread recipes where a strong gluten network is crucial for rise and structure, adding vital wheat gluten can make a significant difference. Vital wheat gluten is essentially concentrated wheat protein. Adding a tablespoon or two per loaf (follow package directions or recipe suggestions) helps compensate for the bran’s interference, boosting the dough’s elasticity and strength, resulting in a better rise and chewier texture. This is especially helpful when aiming for higher percentages of whole wheat flour.

4. Kneading and Proofing Considerations

Whole wheat dough benefits from thorough kneading to develop the gluten structure as much as possible. However, be mindful not to over-knead, especially if using a stand mixer, as the bran can still damage the gluten strands. Pay attention to the dough’s feel – it should become smoother and more elastic. Whole wheat doughs often ferment and proof a bit faster than white flour doughs due to the extra nutrients available for the yeast. Keep an eye on it; over-proofing can lead to a collapsed structure.

Choosing the Right Whole Wheat Flour

Not all whole wheat flours are created equal. You might find:

- Standard Whole Wheat Flour: Milled from hard red wheat, it has a robust flavor and high protein content, suitable for bread.

- White Whole Wheat Flour: Milled from hard white wheat, it offers the nutritional benefits of whole wheat but with a milder flavor and lighter color, making it a great “stealth health” option for picky eaters or recipes where you don’t want a strong wheat flavor.

- Whole Wheat Pastry Flour: Milled from soft wheat, it has lower protein content. It’s better suited for tender baked goods like muffins, scones, pancakes, and quick breads, rather than yeast breads.

- Stone-Ground vs. Roller-Milled: Stone-ground flour often has a coarser texture and may contain more oils from the germ, potentially leading to a shorter shelf life but often praised for superior flavor. Roller-milled is more common commercially.

Adapting Your Favorite Recipes

Ready to try converting a recipe? Start simple. Quick breads, muffins, pancakes, waffles, and cookies are generally more forgiving than yeast breads when substituting whole wheat flour.

General Substitution Guideline:

- Begin by replacing 30-50% of the all-purpose flour with whole wheat flour.

- Slightly increase the liquid (water, milk, oil) – about 1-2 teaspoons extra per cup of whole wheat flour used is a good starting estimate. Observe the batter/dough consistency.

- Consider adding a touch more sweetness (like honey or maple syrup) if you want to balance the heartier flavor of the whole wheat, especially in cookies or muffins.

- Allowing the batter or dough to rest for 10-15 minutes before baking can improve texture by letting the whole wheat flour fully hydrate.

For yeast breads, remember the tips about hydration, potential need for vital wheat gluten, and considering an autolyse step. Don’t expect an exact replica of the white flour version; embrace the unique character whole wheat brings.

Embracing the Flavor and Texture

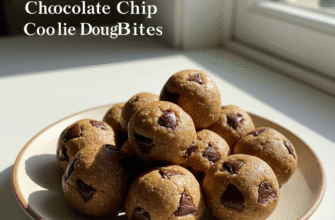

Part of the journey is learning to appreciate the distinct qualities of whole wheat. Its nutty, slightly earthy flavor pairs beautifully with ingredients like oats, nuts, seeds, honey, molasses, spices (cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger), chocolate, and fruits (apples, bananas, berries). Instead of trying to completely mask it, work with it. A hearty whole wheat sandwich bread makes incredible toast. Whole wheat muffins packed with carrots and raisins feel substantial and satisfying. Whole wheat chocolate chip cookies have a delightful chewiness and depth.

Whole wheat flour contains the bran, germ, and endosperm of the wheat kernel. This makes it richer in fiber, vitamins, and minerals compared to refined white flour. Baking with whole wheat is a simple way to add more nutrients to your diet. Remember that storage matters; due to the oils in the germ, whole wheat flour spoils faster than white flour, so store it in an airtight container in a cool, dark place or preferably the freezer for longer shelf life.

Baking with whole wheat flour opens up a new dimension of flavors and textures in your kitchen. It requires a slightly different approach than baking with white flour, focusing on proper hydration, gentle handling, and sometimes employing specific techniques like autolyse or adding vital wheat gluten. By understanding how whole wheat flour behaves and making small adjustments, you can successfully incorporate its wholesome goodness into a wide array of delicious baked treats. Be patient, experiment, and enjoy the satisfying results of your whole wheat baking endeavors!