The world of sweeteners is vast and often confusing. Beyond the familiar white sugar cube, a whole range of options exists, each with its own characteristics, origins, and uses. One alternative that has gained some traction, particularly in health-conscious circles and specific dietary niches, is brown rice syrup. But how does it stack up against the granulated sugar we know so well, or other popular choices like honey, maple syrup, or even high-fructose corn syrup? Understanding the differences is key to making informed choices in the kitchen.

Understanding Brown Rice Syrup

First off, what exactly is brown rice syrup? Unlike table sugar (sucrose) derived from sugarcane or beets, brown rice syrup comes, as the name suggests, from brown rice. The process involves cooking brown rice and then treating it with enzymes. These enzymes break down the complex carbohydrates, specifically the starches present in the rice, into smaller, simpler sugars. The resulting liquid is then strained and cooked down to create a thick, viscous syrup. Its color typically ranges from light amber to dark brown, and its flavor is generally considered mild, less intensely sweet than white sugar, often with subtle nutty or caramel undertones reminiscent of its source grain.

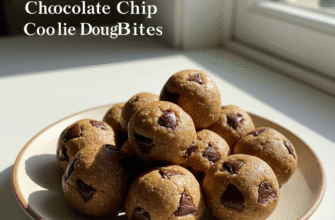

The texture is quite thick, similar to molasses or honey, which influences how it behaves in recipes. It’s not just a sweetener; it can also act as a binder, making it popular in things like homemade granola bars or energy balls.

The Sugar Profile Matters

A crucial difference between sweeteners lies in their sugar composition. Table sugar, or sucrose, is a disaccharide made of 50% glucose and 50% fructose bonded together. Brown rice syrup, however, has a unique profile resulting from the enzymatic breakdown of starch. It contains virtually no fructose. Instead, it’s primarily composed of maltose (two glucose units linked together), maltotriose (three glucose units linked together), and some free glucose. The exact percentages can vary depending on the manufacturing process, but maltose is usually the dominant sugar.

This lack of fructose is often highlighted as a key benefit by those looking to reduce their fructose intake. However, it’s important to look at the bigger picture. While it avoids fructose, brown rice syrup consists entirely of sugars derived from glucose. Glucose directly impacts blood sugar levels. Consequently, brown rice syrup typically has a high Glycemic Index (GI). The GI is a measure of how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food raises blood glucose levels. Foods with a high GI cause a more rapid spike in blood sugar compared to low-GI foods.

Brown Rice Syrup in Comparison

Let’s place brown rice syrup side-by-side with other common sweeteners to get a clearer perspective.

vs. White Sugar (Sucrose)

The most obvious comparison is with standard white table sugar. White sugar is highly refined, providing a clean, purely sweet taste. Brown rice syrup is less sweet and has that characteristic mild, slightly nutty flavor profile. Compositionally, they differ significantly: white sugar is 50% glucose/50% fructose, while BRS is mostly maltose and glucose, with negligible fructose. White sugar comes granulated (or powdered), while BRS is a liquid, affecting how they are used in recipes; substituting one for the other often requires adjustments to liquids and sometimes leavening agents in baking. While both are caloric sweeteners contributing to sugar intake, their impact due to the fructose/glucose ratio differs, though BRS’s high GI means it still causes a significant blood sugar response.

vs. High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS)

HFCS is an industrial sweetener derived from corn starch. Enzymes convert corn starch glucose into fructose. Common formulations like HFCS 55 contain approximately 55% fructose and 42% glucose, making its fructose content even higher than table sugar. Brown rice syrup stands in stark contrast with its near-zero fructose content. Both are liquid syrups used extensively in processed foods and beverages, though HFCS is far more prevalent due to its low cost and high sweetness. Concerns surrounding HFCS often relate to its high fructose load and ubiquitous presence in the food supply. BRS offers an alternative for those specifically avoiding fructose, though it isn’t necessarily a ‘healthier’ swap in all contexts due to its own high GI and caloric nature.

vs. Honey

Honey is a natural liquid sweetener produced by bees from flower nectar. Its composition varies depending on the floral source but generally consists of about 38% fructose, 31% glucose, plus small amounts of other sugars, water, enzymes, vitamins, and minerals. Honey has distinct flavors that range from light and floral to dark and robust, unlike the milder taste of BRS. Both are viscous liquids useful in similar applications, though honey is typically sweeter. Nutritionally, honey contains fructose, unlike BRS, but also offers trace amounts of beneficial compounds not found in BRS. Both are caloric sweeteners.

vs. Maple Syrup

True maple syrup is made by concentrating the sap of maple trees. Its primary sugar is sucrose (like table sugar), meaning it breaks down into glucose and fructose in the body, although it also contains small amounts of free glucose and fructose. Pure maple syrup is prized for its unique, rich flavor, which is much more distinctive than brown rice syrup’s mild sweetness. Like BRS, it’s a liquid sweetener, often used in baking, glazes, and famously, on pancakes. It contains minerals like manganese and zinc. While it contains fructose (as part of sucrose), its overall profile and flavor offer a different experience compared to BRS.

vs. Agave Nectar

Agave nectar, derived from the agave plant, is another liquid sweetener often marketed as a natural alternative. However, it is highly processed and typically contains a very high concentration of fructose – often 70-90%. This is significantly higher than even HFCS. It’s sweeter than sugar, so less might be used, but the fructose load per serving can be substantial. Compared to agave, brown rice syrup offers the opposite profile: virtually no fructose but high in glucose-based sugars. Agave has a lower GI than BRS because fructose doesn’t raise blood sugar as directly as glucose, but high fructose intake carries its own metabolic concerns.

vs. Non-Nutritive Sweeteners (Stevia, Monk Fruit)

This category is entirely different. Sweeteners like stevia (from the stevia plant leaves) and monk fruit extract (from the monk fruit) provide intense sweetness with essentially zero calories and no impact on blood sugar levels. They are not carbohydrates. Brown rice syrup, being derived from rice starch, is a carbohydrate source, provides calories (similar to sugar), and has a significant GI. The taste profile also differs greatly; stevia and monk fruit can sometimes have a slight aftertaste that some people find noticeable, whereas BRS offers bulk and a mild sweetness more akin to traditional sugar syrups.

Important Consideration: It’s worth noting that rice products, including brown rice syrup, can potentially contain levels of inorganic arsenic absorbed from the soil or irrigation water. Regulatory bodies monitor these levels to ensure safety. Consumers concerned about arsenic exposure may wish to research specific brands regarding their testing practices or moderate their overall intake of rice-based products as a precaution.

Pros and Cons Summarized

Choosing a sweetener involves weighing various factors.

Potential Advantages of Brown Rice Syrup:

- Fructose-Free: Suitable for individuals specifically aiming to limit fructose intake.

- Vegan: Unlike honey, it is plant-derived and suitable for vegan diets.

- Mild Flavor: Its less intense sweetness doesn’t overpower other ingredients, making it versatile in some recipes.

- Liquid Form: Easy to incorporate into dressings, sauces, and beverages. Acts as a binder in bars and baked goods.

Potential Disadvantages of Brown Rice Syrup:

- High Glycemic Index: Causes a relatively rapid increase in blood sugar levels, which may be a concern for some individuals.

- Caloric Sweetener: It contributes calories and counts towards total sugar intake, similar to other sugar syrups.

- Potential Arsenic Content: Like other rice products, it may contain inorganic arsenic (see warning blockquote).

- Lower Sweetness: More syrup might be needed to achieve the same level of sweetness as sugar, potentially increasing calorie and carb counts.

- Processed: While derived from brown rice, it undergoes significant enzymatic processing.

Using Brown Rice Syrup in the Kitchen

Brown rice syrup’s unique properties lend themselves well to certain culinary applications. Its viscosity makes it an excellent binder for homemade granola, cereal bars, and energy bites, helping hold ingredients like oats, nuts, and seeds together. In baking, it can add moisture and a chewy texture to cookies and some cakes, although recipes may need adjustments to liquid content and potentially baking soda/powder, as it’s less acidic than honey or molasses. Its mild flavor works well in marinades, glazes for vegetables or tofu, and some salad dressings where a subtle sweetness is desired without the distinct notes of honey or maple syrup.

However, remember its lower sweetness intensity compared to table sugar. Direct substitution might result in a less sweet final product unless the quantity is increased, which also increases overall liquid and sugar content. Experimentation is often key when incorporating it into recipes designed for other sweeteners.

Making the Choice

Ultimately, there’s no single “best” sweetener for everyone. Brown rice syrup presents a unique profile – primarily its lack of fructose combined with a high GI and mild flavor. It offers an alternative for those avoiding fructose or seeking a vegan liquid sweetener with binding properties. However, it’s still a caloric sugar source that significantly impacts blood glucose. Comparing it to white sugar, HFCS, honey, maple syrup, agave, or zero-calorie options highlights that each has distinct compositions, flavors, processing levels, and effects in the body.

The decision often comes down to individual dietary goals, taste preferences, the specific recipe requirements, and considerations like glycemic impact or fructose content. Like all concentrated sources of sugar, moderation remains a sensible approach regardless of the type chosen.